Doctorate, interrupted

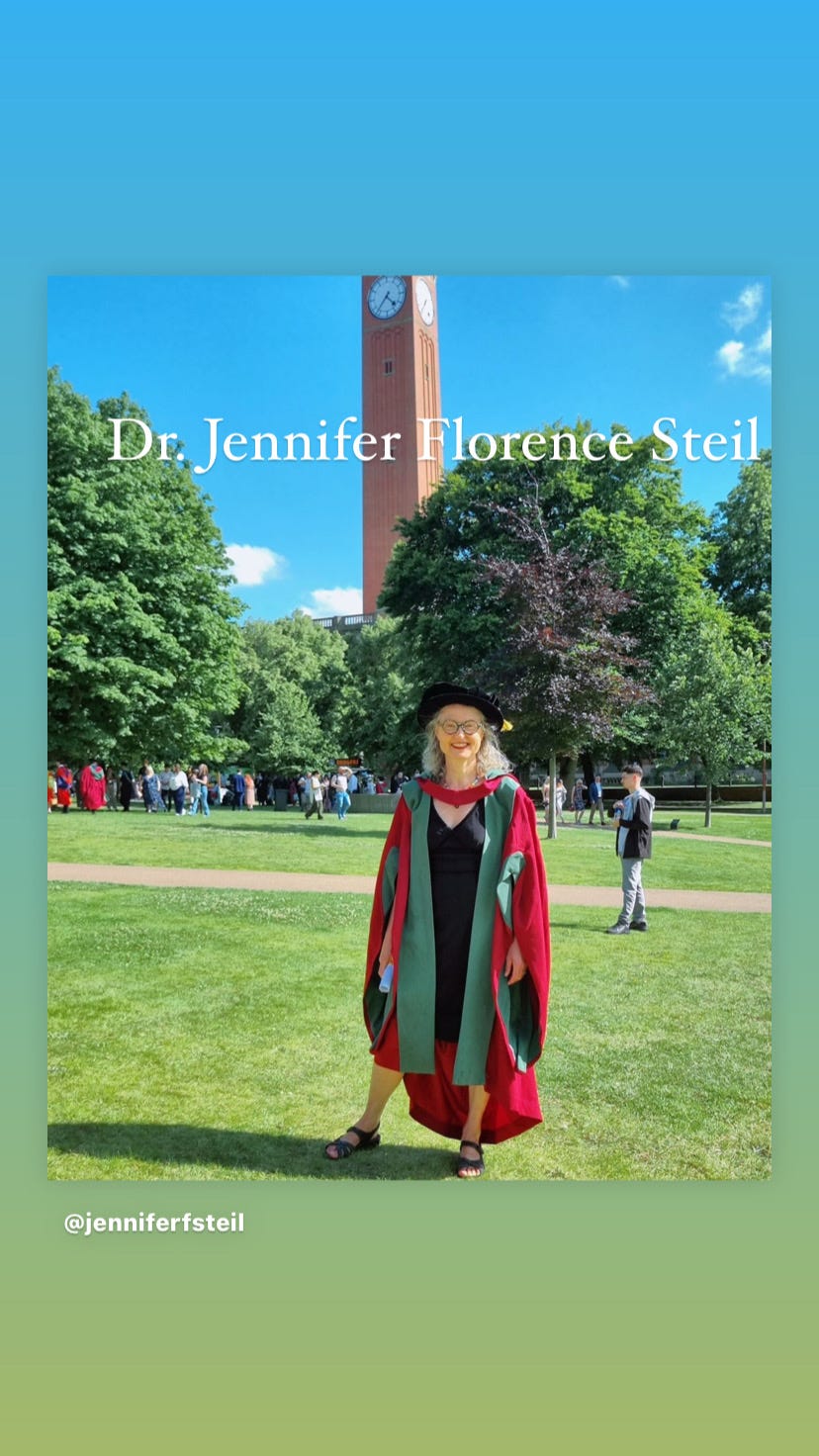

As I attend my PhD graduation ceremony in Birmingham, England, I reflect on the tortuous (and sometimes torturous) path that led me here.

I write this from the London home of our dear and generous friends, Patrick and Louise, who took me in when I was first diagnosed with ovarian cancer, and allowed me to stay with them for the first several months of chemotherapy. Every room contains memories. The bathroom where Theadora first cut off my hair, the tub where much of what remained washed down my body. The room where.I wrote every morning, feeling my way through what was happening to and in me. The green carpet where I lay unconscious three days after my first chemo. The kitchen where I danced a Swan Lake barre in the mornings when it was abandoned.

This morning, I danced that barre once more, without the cancer.

I didn’t need to attend the graduation ceremony for my PhD. It would have been easier to receive my diploma by post. Attending my degree congregation meant traveling from our village to Nîmes on the day the Tour de France passed through it, hopping a train to Paris, taking the Eurostar to London, and another train up to Birmingham.

While I passed my Viva last December and had the final draft of my thesis accepted into the university library in March, the accomplishment didn’t feel real. There had been no ritual, no public ceremony, no classmates to celebrate with me. I wondered vaguely if I deserved the degree. I wondered if I had dreamed the entire thing, all five years of it.

Nothing in my life changed when I finished my thesis. I still got up every morning to write. I continued wandering the French mountains while dreaming up new sentences, cooking dinner for my family, and picking out vegetables at the Saturday market. I had no colleagues, no academic job, no professors to shake my hand. Most of the people with whom I had started my PhD studies with had already received their degrees. I had taken a year’s medical leave during my first chemotherapy and surgery and fallen behind.

During my all-too-brief remission last summer, I went back to work, burying myself back in my thesis, beavering away at the manuscript with a new sense of urgency. If this cancer was going to get me, I was going to die a doctor. That PhD would be on my tombstone if nowhere else. I don’t know why this mattered, but it did. It was unfinished business.

And then the cancer came back. I restarted chemotherapy with a new drug. But by then I was almost done with my thesis. Days when I was well enough, I edited and tweaked and restructured until finally I was finished.

In the middle of that last round of chemo, just before Christmas, I passed my oral exams. There was no joy, no exhilaration, or pride in the completion. It was like publishing a first book, when you think your entire life is going to change and then it doesn’t.

I had begun my doctoral research in great joy, propelled by my love of academia, research, and writing. I chose to do the degree because I knew how much I would love the academic rigor and community. I wanted to write a book with colleagues around me. I wanted to learn how new fields of research would influence my writing. I also knew it would be easier to secure a teaching job with a PhD.

Having never attended a UK university, I was somewhat taken aback by the vast anonymity of the system, of how different the structure was from that of US universities. The Film and Creative Writing department held no opening receptions, offered no opportunities to meet the professors and other creative writers. There were no weekly literary events to foster relationships. Those I met I did so by accident, because they had supervision before or after me. Or because I directly contacted professors I wanted to meet by email. I knew I would be doing my work alone, but I had hoped for more community-building structures, like those at the cozy liberal arts colleges in which I formed lifelong friends. I had looked forward to long discussions about writing over coffee. This, for the most part, did not happen.

Despite this, my first six months of work were blissful. I adored my supervisor, who sparked new ideas and opened doors in my head and my writing every time I talked with him. I loved the work itself, crammed as it was into my daughter’s schooldays, my teaching schedule at Bournemouth University, and early mornings.

And I did meet some fellow researchers outside of my department, those who were also pursuing doctorates via distance learning. We all began together with two weeks of orientation and training, which I loved. I connected with a handful of people who were working in other fields, music, English, Shakespeare studies, and theology. I have kept these friends.

My work was first interrupted by catastrophic nerve damage due to an injury to my cervical spine. (Kids, yoga can be dangerous). This caused me relentless, disabling head pain for more than three years. I ended up in the emergency room four times before I finally got to see a neurologist, in so much pain it felt hard to breathe. He gave me medication that helped just enough to keep me from jumping out a window to end it all, but not enough to allow room for pleasure or joy. In the middle of this, we moved to Uzbekistan, and I continued to see my supervisor online.

Oddly, only when I was diagnosed with cancer did this pain begin to ebb, as if it realized I had greater threats to my life to worry about. I don’t want to write much more about the nerve pain because it likes attention, and the more I think about it the more I feel at risk of resurgence. It still pops in to visit. It was an adverse reaction to a new drug prescribed for my nerve pain that got me evacuated to London, where the cancer was discovered almost by accident.

Thus while my doctoral studies were not the unmitigated joy I had dreamed they would be, they did provide me with constant challenges and new ideas.

On our way up to Birmingham, I worried that the day would feel too lonesome. My supervisor was hiking in the Alps. No other professors I knew would be there. I didn’t know anyone else who would be receiving her degree at the same time. On a brief morning walk-run, all of my previous commencements returned to me: Oberlin, Sarah Lawrence, Columbia University. All gloriously sunny days, all immensely happy (although I was not happy to be leaving Oberlin—I was no fool. I knew what a luxury my four years of education had been, knew that ahead of me was taxes and probably poverty).

But standing in line to receive my robes, I saw that the man in front of me was also getting PhD robes. “What did you study?” I asked.

“Creative writing,” he said. “Actually, I think I recognize you! I saw you coming out of supervision.” So there was a friendly face after all.

My first emotional moment came when the dressers approached me. I hadn’t expected that someone would actually slip my arms into my robes. Tears pricked my eyes as they fastened the various straps and found a hat that fit me. “You look like Professor Trelawney,” Tim said when I emerged from the building in my finery. I did indeed feel ready to practice magic.

The sky was clear and blue. Sunny but not hot. Grinning graduands wandered the campus in their various robes. I showed Theadora and Tim, who had never seen the university, the Film and Creative Writing house, the library, the College of Arts and Law. The university lacks the charm and beauty of Oxford or Cambridge, but it has its own red-brick respectability.

Everything was incredibly efficient. There were no queues as I picked up our tickets, bought sandwiches, and had formal photos taken.

The ceremony itself took place in the Great Hall, where the stained-glass windows and high arched ceilings made it feel like a cathedral. There were trumpets. I sat in a row of other doctoral scholars, next to a woman from York named Petra, who had done her research in American films. I found another familiar face, a Russian woman named Olga I had met over drinks before heading to Uzbekistan. The professors processed solemnly down the aisle in their own robes, taking their place at the front of the cathedral.

Then it was our turn. When my name and the title of my thesis were read aloud in front of hundreds of people, I began to feel that maybe, my accomplishment might be real.

Congratulations, Jennifer. Your accomplishment will continue to sink in as time passes.