How the French do books

We interview editors from four French publishing houses. Literary merit is their only criteria for buying books, they say. “The commercial department cannot say ‘don’t do it.’”

Before I launch into this week’s column, I must acknowledge the suffering of all of you living in Los Angeles. I have been horrified and heartbroken to watch the fires take away so many lives and homes and hopes. Please know that you are in my thoughts. I have felt helpless to offer any assistance, being so far away and without material wealth. However, I do invite any of you needing to escape for awhile to a refuge in our guest rooms. The air is clear here, and perhaps some time in France would give you a chance to sort out a new home or simply the space to collect your thoughts. Let me know if there is something I can do.

As you know, I have been traveling around Paris and Arles with a group of 25 MFA students of creative writing from Rosemont College. Some of these students are also pursuing an MA in publishing. Our program thus involved visits to esteemed publishing houses and conversations with a few of their top editors. I thought our conversations would interest the writers and readers among you, as well as those of you interested in the contrasting cultural landscapes. The differences between the French and American publishing industries perhaps suggest differing underlying values of the countries. You may draw your own conclusions.

France has 10,000 publishing houses, 20 major publishing houses, and three major publishing groups. There are 24 independent publishers. Books are the biggest sector of the creative economy after videogames. The French do not read or want ebooks—they prefer print.

The country offers 759 state grants for authors, 1,108 grants for publishers, 369 grants for bookstores, 359 grants for literary agents, and 86 grants for libraries. There are 7,300 literary festivals in France, where readers mingle with authors. They are family affairs; people take their children.

In Arles, we had the privilege of meeting with two editors from Actes Sud who specialized in acquiring foreign fiction. One of the most respected publishers in France, Actes Sud has a vast catalogue of French and international books. They translate and publish Siri Hustvedt, Marilynne Robinson, Paul Auster, Percival Everett, Ann Patchett, Salman Rushdie, Jodie Picoult, Don Delillo, Russell Banks, and Anne Enright. They are also one of the few publishers based outside of Paris.

https://www.actes-sud.fr/

Their offices are breathtaking, not least because they include a church. Alongside the church is a warren of beautiful rooms built of wood, each with its own library, and outside terraces interspersed throughout (I doubt Parisien houses have these!). It is the kind of work space I crave. They use the church and other spaces to exhibit artwork.

The editors each described her career path in publishing and talked about the kinds of books she loves and seeks. They emphasized their commitment to authors they selected. “If a first book doesn’t sell well, we don’t give up on the author,” they said. If they love an author’s work, they build up that author. This impressed me, as it isn’t how publishing in the US seems to work these days. So many authors are shuttled from publisher to publisher, with little sense of security or longterm support. If an author fails to produce an airport bestseller, she is often discarded.

Independent bookstores are flourishing in France, these editors said, because book prices are fixed. Amazon and other online sellers cannot reduce book prices to undersell the bookstores, stealing their business. I thought this was a brilliant move, suggesting the value France places on physical, independent bookstores. Because ebooks and print books cost the same, print book sales have not been threatened by digital sales.

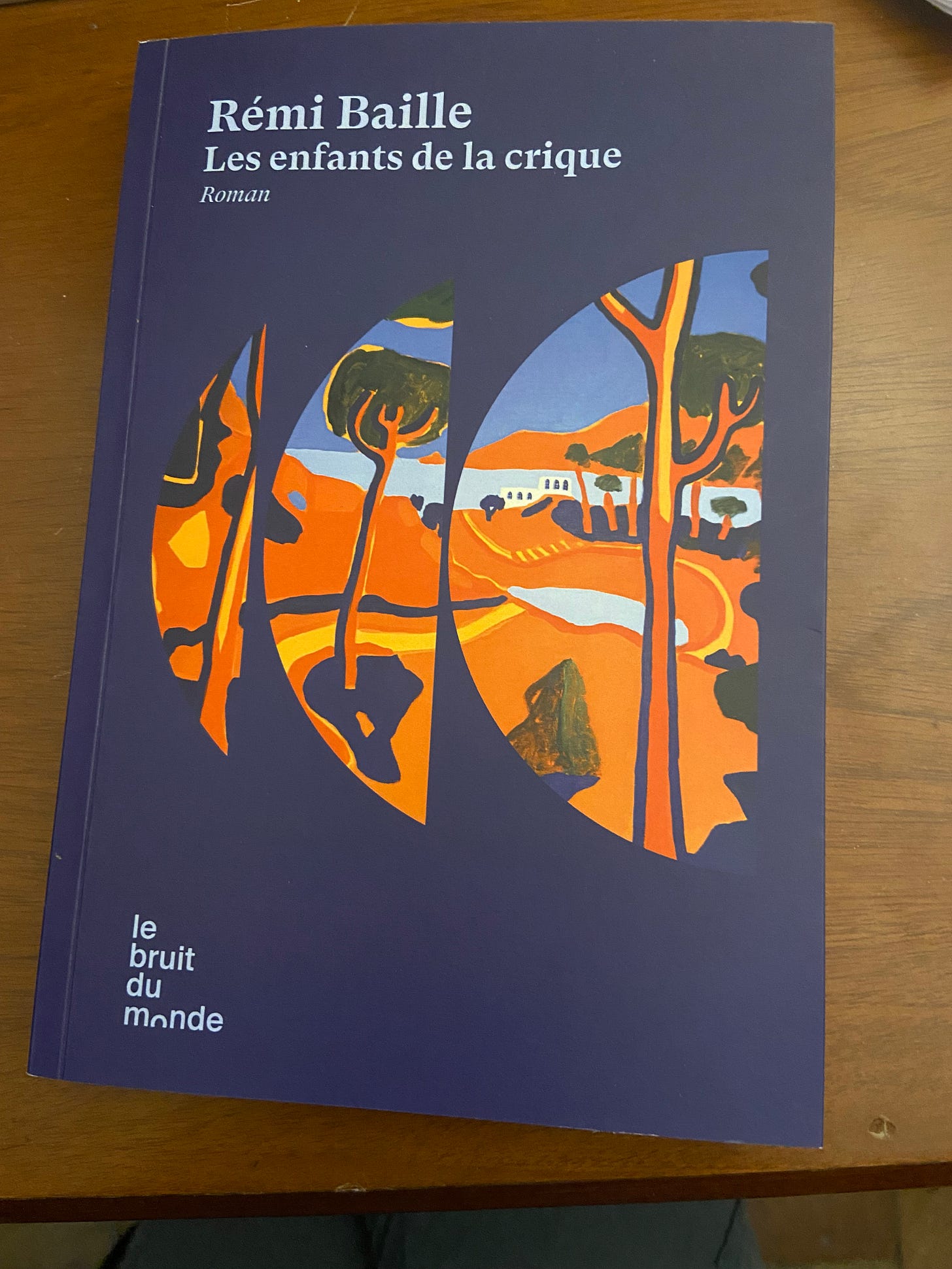

The following day, we met a co-founder of le bruit du monde, a publishing house based in Marseille. She previously worked in Paris, for Gallimard, one of the biggest and most prestigious houses, but eventually wanted to create her own house in a different, vibrant city. She is passionate about international literature, wanting to share with French readers “realities they would not otherwise experience.” She also seeks Francophone literature from abroad—Africa, Quebec, and elsewhere. She emphasized her longterm commitment to authors she publishes. Le bruit du monde thus publishes a diverse array of award-winning authors, including Rémi Baille, Sîàn Hughes, Alice Kaplan, Marion Lejeune, Aslak Nore, Sara Mychkine, and Anna Hope. The covers of these books are distinct and beautiful—check them out on their site:

https://lebruitdumonde.com/maison

https://publishingperspectives.com/2021/03/gallimard-publisher-opens-new-house-in-marseille-covid19/

The last two editors we met work at houses that are part of Editis, the second largest French publishing group, with 55 imprints. Walking into their offices reminded me of the very first time I walked into Penguin Random House in New York. Its enormity awed me.

In a large conference room, editors from julliard and sous-sol (not sure what French publishers have against capital letters) told us the history of their publishing houses and the kinds of books they adore. They emphasized the importance of literary prizes. When someone walks into a bookstore not knowing what they want, they will most likely pick up a book that has a Prix Goncourt or Prix Femina sticker on it. Thus these editors were focused not on which books seemed commercial, but on which books were likely to win one of France’s eight literary awards.

Julliard was founded in 1941 and has changed hands several times. Themes currently important to them include ecofeminism and the impact of generational violence. Its authors include Fouad Laroui, Abubakar Adam Ibrahim, Françoise Sagan, Antony Sher, Philippe Bresson, and Patrick Grainville. https://www.lisez.com/julliard/1

Sous-sol publishes Louise Erdrich, Martin Amis, Jill Lepore, Julian Barnes, Deborah Levy, Joseph Boyden, Nellie Bly, as well as our neighbor and friend Robert Crumb.

https://editions-du-sous-sol.com/

One student asked about the dearth of Black voices in publishing. The editors acknowledged the severity of the problem, but didn’t seem to have a clear plan for increasing inclusivity of people of color beyond encouraging them to “have the confidence to send in their manuscripts.” Clearly the problem goes beyond publishing, has its roots in the whole construct of society. No one can “have the confidence to send in their manuscript” if they are never taught their voices matter, if they are ghettoized and do not have equal access to education, mentors, money, and time. The whiteness of publishing is an issue in both the US and France.

Another student asked whether an editor could buy a book without the support of the marketing team, and the editors firmly stated that they absolutely could and did. In the US, it has been my experience, editors require the support of an entire team before they can commit to a book. This is not the case here. “When we love a book, we publish it. We can always work around the budget,” they said. “The commercial department cannot say ‘don’t do it.’” It was refreshing to hear that here the literary value of the work is more important than its commercial worth.

Managing expectations of eager writers, these editors reminded us that they publish less than 1 percent of books submitted to them. “During the first covid lockdown, one out of three French people submitted something,” one of them said. “Their chances were small.”

Perhaps French publishers are more willing to take literary risks because they pay smaller advances. When asked what kind of advances they offered their authors, they said it was uncommon to pay an author more than 3,000 euros. Few French authors make their living solely writing books.

It also must be acknowledged that French and American markets are vastly different, not only in size. Most French authors do not have agents, but submit directly to publishers. Some, like Actes Sud, require hardcopy submissions. Close to 40 percent of books published in France are translations from other tongues, whereas about 3 percent of books published in the US are translations. In fact, the number of translated books in all genres published in the US has fallen more than 8 percent since 2016. I can’t help but wonder what this says about an interest in and willingness to vicariously experience foreign cultures and minds.

I have more to say about the end of our trip, about friends and food and travel. But I don’t want to test your patience, so will save those. I will add, however, that if anyone requires an excellent and personable tour operator here in France, especially for academic groups, please contact Sébastien Linden. He not only created a diverse and spectacular program, but he made sure that students with celiac disease had gluten-free food and restaurant recommendations, and never made them feel their needs were an inconvenience. He even miraculously found gluten-free galette de roi, the famed epiphany pastry. He looked after all of us like a papa duck, constantly counting us to make sure no duckling had wandered off. We adored him.

https://lindenandswift.com/en/about/

We had the honor of accompanying Jennifer, Sébastien, and the director of the Rosemont College programs, Carla Spataro, on this journey. Jennifer is spot on in her assessments, and the students had an experience of a lifetime. Well done!

Love this! Fascinating and gorgeous photos!