I might be wrong about everything

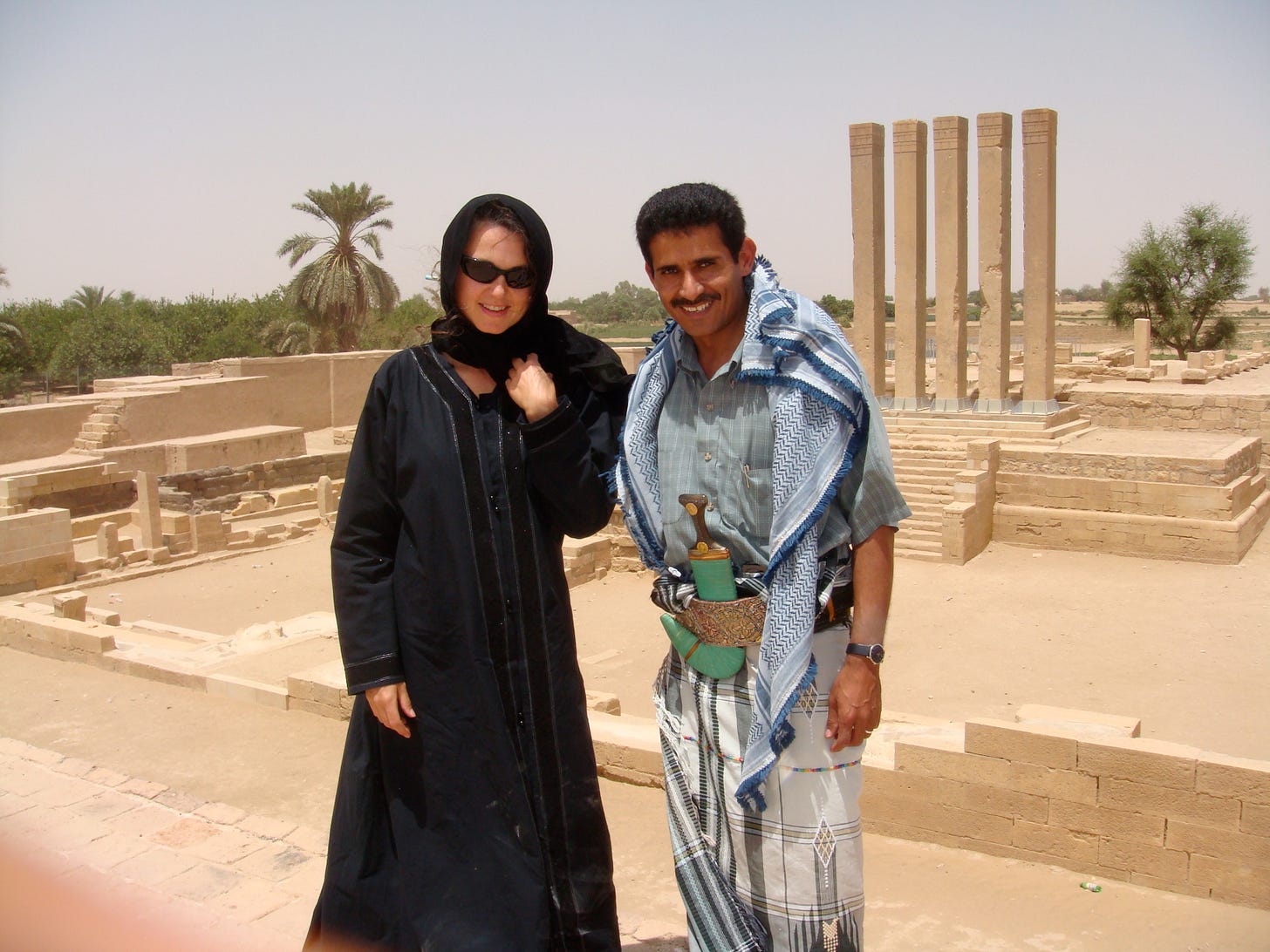

Moving to Yemen in 2006 upended all of my assumptions about the world.

Not until I moved to Yemen in 2006 did I realize how American I was. When I lived within America, I resisted being defined by my country. I was often in furious disagreement with the government, protesting and signing petitions. I did not align myself with my country when my country sold weapons to other nations, bombed other countries, or made it easy for kids to get their hands on automatic rifles. I could not align myself with a country that invested so much taxpayer money in the military industrial complex, that kept nuclear weapons at the ready. I could not align myself with a country founded on the genocide of its indigenous people.

I was more likely to identify myself with smaller geographical locations and groups. I was happy to align myself with New York City in all its glorious diversity, its arts, its chaos. I was proud that one of my home states, Vermont, elected Bernie Sanders, the only socialist senator. I defined myself in a million different ways, but never simply as an American. It felt too broad a term to have any real meaning. When I was growing up, the only people who flew American flags in their yard were Republicans. I had no idea why this was the case, but it persuaded me that patriotism was not something for liberal democrats. Our job was to critique the government, not blindly support it.

Yet I also had a childlike trust in the structures of the country, a belief that the grownups knew what they were doing. I trusted that I could drink the tap water, have a say in an election, have access to uncontaminated food, and file a police report if anyone hurt me. I naively trusted that our intelligence services were working for our benefit.

When I moved to Yemen in 2006, every assumption I had about the world was upended. In Yemen I couldn’t trust that the water was drinkable or food safe to eat. I couldn’t assume anyone around me shared my beliefs. I couldn’t assume that my actions and beliefs were the normal ones, the right ones.

I did not grow up religious, although I had friends of all religions. I was accustomed to diversity of beliefs. Never had I lived in a place where everyone belonged to the same religion, where religion guided every aspect of life. I had to become a listener more than a talker, to try to wrap my mind around how my new friends saw the world.

In Yemen, family is of the utmost importance, followed by tribe. Women live with their families until they married, and then join the families of their husbands. No one ever lives alone. I had lived alone in New York for the previous seven years. I loved living alone. In fact, I didn’t think I could ever bear to live with anyone else again. I didn’t think of myself as an outlier; large percentage of New Yorkers live alone. I was also happy living alone in Yemen, enjoying the solitude and privacy I found in my own home after a long day editing the newspaper.

One day, I became so ill I could not leave my bed. I called in sick for the first time. Less than an hour later, two of my female reporters showed up at my door. “We are worried about you,” they said. “How can we help?” When they came inside and discovered that no one else lived with me, they were shocked. “We didn’t realize you were living alone!” they cried. “This is terrible! You should have told us! You should have come lived with us!” They could not imagine that this was something I had chosen, just as I had been unable to imagine living in close quarters with my extended family.

Soon after that, I came home from work to find a German woman crying on my stairs. The landlord had evicted her from her nearby apartment and she had nowhere to go. Move in with me, I said immediately without thinking. I have plenty of space. So she did. We became fast friends. Anne-Christine was also a vegetarian and cooked delicious aubergine curries and all kinds of other dishes I would never have had the energy to make after twelve hours at work. We traded stories of secret love affairs and the trials of our workplaces. I realized that I loved having company at home. When Anne-Christine left for Germany, I mourned. I took in a German artist, an Indonesian-Dutch researcher, a Dutch diplomat, and a Scottish writer. Anyone I met who needed a home. I loved knowing that when I returned from work depleted there would be someone with whom I could share a drink and invigorating conversation. Everyone was doing such interesting work. We lived well together, respecting each other’s privacy and independence but enjoying our togetherness. Look at me now, I thought, I’ve become communal!

I learned many other things, darker things. When on my way to work one day my taxi driver began masturbating at the wheel, I leapt out at an intersection and walked the rest of the way to work. I told my female reporters what had happened, and they were not surprised. This happens to us all the time, they said. This is what men are like. They couldn’t report harassment or rape, because they would be blamed for it. They could not assume anyone would protect them from violence. We began writing about this at the paper, especially about a woman imprisoned unfairly who came forward to say she was raped by the guards. Our stories may not have made a difference, but the paper was the only tool we had.

There were many smaller discoveries. Many people thought using toilet paper to clean their bottoms, rather than rinsing them with water, was disgusting. Was it possible we Americans were wrong about toilet paper? I began to question everything.

I also began to realize that despite what I had thought, America had profoundly shaped me. I believed in elections, in democracy, in freedom of speech and religion. I thought that overall our country was a force for good, a belief that has since faced constant challenges. I believed that I had the right to make independent decisions about my life, to report crime, to choose whom I married. I took these things for granted. (I also believed in toilet paper, though now I’m convinced bidets are definitely the way to go, especially as they are kinder to trees).

After nearly a year in Yemen, I had to renew my passport, which required a trip to the US embassy. I had never been to an embassy before. When I saw the familiar flag flying over the building, I found myself unexpectedly emotional. How lucky I was! I had a country that would give me a passport that allowed me to easily enter and leave the country, that would rescue me in the event of calamity, that had reliable elections. I had not realized how enormous were the privileges granted to me by the accident of where I was born. These were not privileges shared by my reporters and friends. The women didn’t even have their own passports, but were represented on the passports of their fathers or husbands. Yemen was no utopia. I could not align myself with the corrupt government of that country; I still cannot align myself with any one country. But there was also so much to love I had not expected: the instant hospitality, the generosity, the open heartedness of all the Yemenis I met. I have never felt more welcome anywhere.

Since then, my rosier views of the United States have been constantly challenged. I understand our critics more deeply. From here, now, it appears that the entire country has lost its mind. How could so much of the population allow themselves to be brainwashed by a mad criminal? How could Americans allow women to lose the rights to their body I had always taken for granted? How could they still cling to guns and send money to the Saudis?

Yet my views on the American people I know and love have not changed. There are millions of extraordinary people in the United States, and I don’t mean to diminish them in any way. I know they are fighting for positive change. We are more than our countries.

Now other countries have granted me new privileges. In both the United Kingdom and in France I have access to free healthcare. I was able to give birth without paying for it, to have surgery without bankrupting my family, to receive first-rate cancer care without filling out insurance forms or making copays. It is now impossible for me to imagine living again in a country without universal healthcare. It is impossible for me to imagine living in a country that makes higher education unaffordable for most people.

While the years since I left the country have continued to dismantle all of my assumptions and beliefs, I cannot deny that certain beliefs remain. I love the exceptional education offered by US universities. By this I mean that I love that they grant students the freedom to study whatever they want for two years before declaring a major. Students need to be able to explore, to discover new passions. I benefitted from this, learning about environmental science, dinosaur bone structures, and psychology before settling into my theatre major. What I learned in that environmental science class still guides how I choose the food I eat.

I don’t think we should require 18-year-olds to know what they want to do with their lives. I appreciated having a full four years of education. I was surprised to find that in the UK students usually study just one subject, for just three years. Students studying medicine don’t ever learn about literature. Yet all the things literature has to teach us would be beneficial to doctors: insight into the minds and bodies of others, appreciation for a diversity of views, and understanding of human nature. At least education is still much cheaper in the UK, within reach of more people.

As I have written before, every country has its challenges. I do not seek perfection; such a thing is not possible in a world governed by humans. I am glad to have the opportunity to constantly learn new ways of doing things and seeing the world. New views on the meaning of life.

Perhaps the most important thing I have learned about assumptions over the years is: Try not to have any. Be open to changing your mind and the way you do things. Understand that much of what you believe is accidental, depending on where you were born, at what time, in what body, to what parents, and in what community. Allow yourself to be wrong.

I’d love to hear what assumptions you have had about the world that have changed and what changed them. I have been delighted to see so many new subscribers lately, and I hope that we will form a community of the liminal here, sharing our experiences and questions. Feel free to tell me what I am wrong about.