Navigating the unknowing

How do you know when it's time to start writing letters to the child you will leave behind?

None of us know how much time we have on this earth. Cancer just reminds us how little might be left. I don’t know how much longer I will survive; the statistics are against me, but some people do. Research continues. New treatments arrive. My cancer is unique, with its own narrative.

Yet I cannot turn the pages faster to see where the narrative will end. I cannot skip to the last page. The liminal space I have been inhabiting recently—knowing the cancer is back but not having re-started treatment yet—has been uncomfortable. There is the physical discomfort: my bowels stopped working at the end of August, and only six sachets of osmotic laxatives per day keep things moving through me; my stomach is swelling with ascites; I’m often nauseated or exhausted. It’s not a state that can be maintained indefinitely. I just hope it can be maintained until my next scan on October 24; the results will offer us information to guide our next steps.

The psychological discomfort is greater. Each day I feel paralyzed with indecision about how to best divide my time. If I am going to live many more years, I have the luxury of working fulltime writing novels, essays, and stories. But if I have months rather than years, as my oncologist has suggested, then I probably should get cracking writing letters for my daughter to open on her birthdays once I am gone. I should probably find a literary executor, give Tim all my bank details, write letters to everyone I love so they know what they have meant to me.

I talked about this with Troy, my beloved cancer psychologist. “Make a pie chart,” he suggested. “Include everything you value and then spend a percentage of your time on each one. So maybe you spend 80 percent of your time on your novels and 20 percent writing to your daughter.”

It’s a very simple suggestion. Troy is full of practical, actionable suggestions. Things I should have thought of but haven’t.

So I made a pie chart. It includes: writing, reading, time with Tim and Theo, writing letters to Theo, planning for the end, friends, community, exercise, and eliminating the chaos in our house. Since then, I have made time for most of these. I have already written 23 typed pages of letters to Theo. I have finished unpacking the 41 boxes of books that were stacked in my office and given away most of my clothing. (We are making the Red Cross charity shop near us very happy). This week I have spoken to friends nearly every day. I have made an effort to find community locally. Every morning I climb the mountain or do ballet and yoga. Moving my body has never been optional. Most importantly, any moment Theo wants to spend time with me or talk, I drop everything.

Saturday night, Tim and Theo and I sat at the table long after finishing dinner, involved in an intense conversation about the state of the world. We talked about nuclear war, the Cold War, the concept of mutually assured destruction, Sudan, Gaza, Israel, religion and how it is wielded, politics, morality, and the environment. In retrospect, a bit much for a young person who needs hope for the future. But it was Theo who was driving the conversation. She had questions, and we answered them. She cried. I wish we could tell her that the world is not how it is.

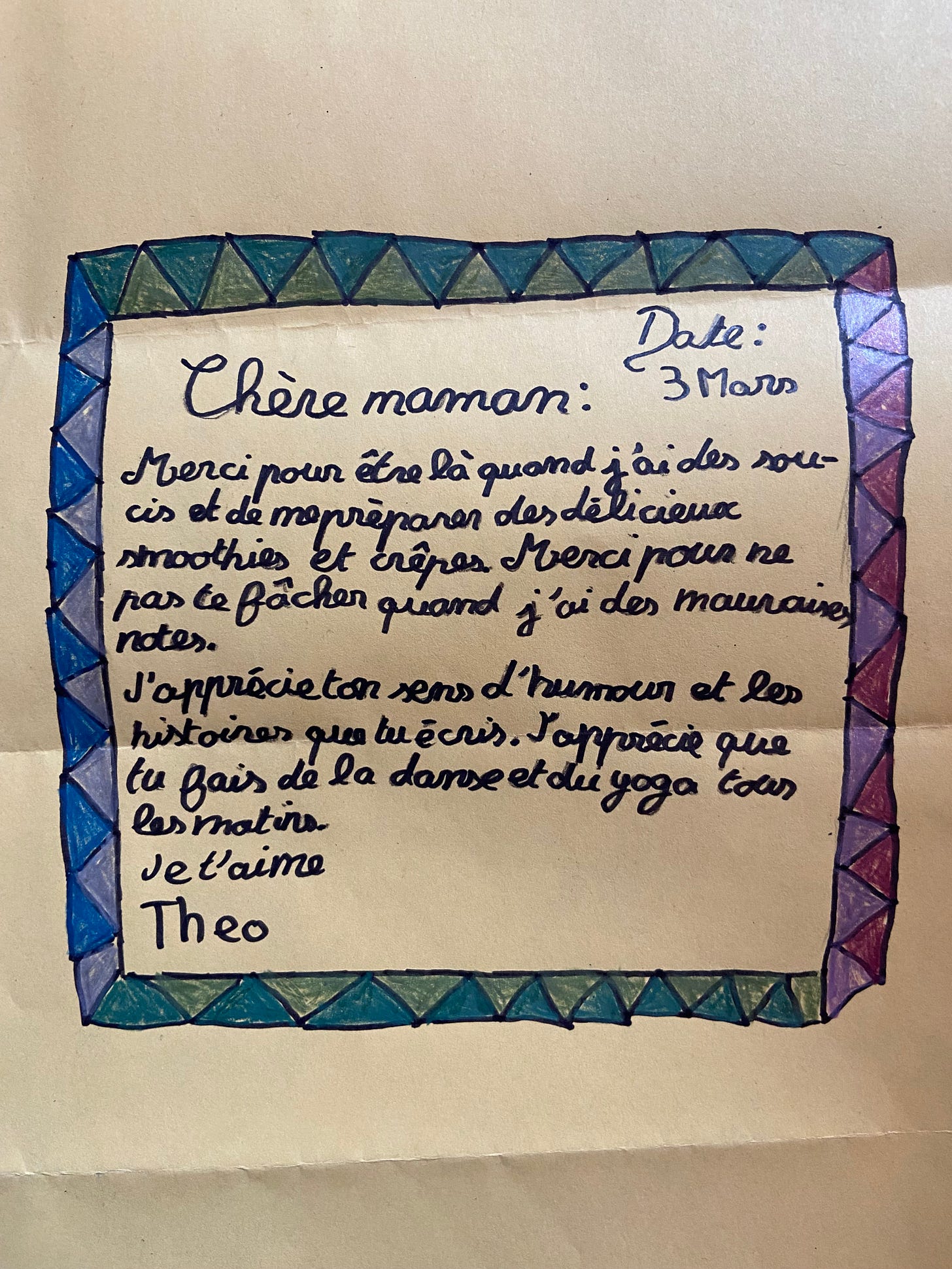

I can’t remember how we transitioned into talking about me. But I ended up confessing I was writing her letters for her birthdays, but often felt like I wanted her to read them now, so we could talk about them.

“I want to read everything while you are alive,” she said, crying again. “I want to be able to talk about everything with you. I want to be able to ask you questions. I want to read your journals and letters before you die, whenever that is.”

“Okay,” I said. “Okay.”

I probably thought it would be a nice idea to leave her letters to read after my death because that’s what dying mothers do in movies. (Dying mothers in movies seem to have a lot of time). But leaving letters with anything interesting in them would indeed only frustrate the reader, who would want to ask questions. It doesn’t make sense.

I contain most of the memories of Theo’s early childhood. Those memories will go with me if I don’t give them to her. Many I have written in journals, but there is a vast library of more in my head. One of my projects is trying to collect all of my memories of her life.

There will be hard things for Theo to read about my own earlier life, things I might ordinarily have waited until she was older to tell her. Just as I also would prefer to wait until she is older to die. I don’t want to be the cause of grief in her life. I want to be a source of joy, inspiration, and comfort.

She still treats me like she always has; She asks me to make her French toast, talks with me about her passions, complains about teachers and classmates. She gets cross with me if I don’t immediately understand something. She rings to tell me trivial things. I treasure every moment. Almost all the time, I manage to be myself around her; I don’t want her to remember me sad or depressed. I want her to remember me happy, working, funny. I want her to remember me incandescent.

But I can’t choose how she will remember me. Just as my mother did not choose for me to remember her consumed by dementia. It has been so many years since my mother was herself that I struggle to remember what she was like before this disease took her away. This feels to me the greatest tragedy. That my memories of her have been stolen, written over.

I hope Theo will not need to remember me any time soon. I still hope for many more years. None of the thoughts expressed above mean that I am ready to surrender, that I am in any way giving up.

I will wait as long as I can. As long as I possibly can.

Beautifully written by a truly incandescent woman.These posts are beneficial for everyone that cares about you. Thank you for sharing. 😘

You are inspirational and incandescent! Please keep writing more and more! D xx